Chapter 2

This weeks lecture was dedicated to The Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest known myth ever discovered. The assignment included reading of the epic, which i approached with interest – but, as i later realized my reading had been quite superficial. The lecture, however, was profound and striking. Listening to the discussion between Professors Puchner and Damrosch, I was amazed by the depth and diversity of literary analysis. I hadn’t imagined that such broad and complex questions could be asked about an ancient epic, nor that such a wide range of interpretations could emerge. It felt like an archaeological adventure – an excavation of meaning across time. For me, this was the first truly rich and intellectually engaging literary discussion I’ve witnessed. It was awakening, inspiring, and honestly – delicious.

Contents

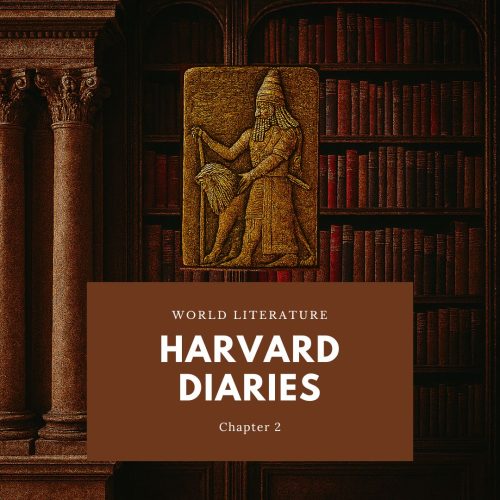

The origins and final form of the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh was the most celebrated literary work of the ancient Near East during the second and early first millennia BCE. After flourishing four centuries, it vanished from the cultural memory for nearly two thousand years – until its rediscovery in the 18th century.

During that era, a group of explorer-archeologists-adventurers excavated the ruins of Nineveh, the ancient capital of Assyria. Nineveh yielded clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform script, including fragments of the Gilgamesh epic.

The Standard Babylonian version, compiled around 1200 BCE and attributed to the scribe Sin-leqi-unninni, became the most complete and widely circulated form of the epic. It spread for beyond Mesopotamia: fragments have been found in regions corresponding to modern-day Western Iran, Turkey, and even Megiddo, just north of Jerusalem. Over centuries, the epic was translated into several languages, reflecting its broad cultural reach. Yet by the 300-200 BCE, the cuneiform writing system had disapeared, and with it, the epic was lost – until modern archeology revived it.

Sin-leqi-unninni worked within a tradition that stretched back 800 years of written transmission, and even further – 500 years of oral storytelling – to the historical Gilgamesh, a king who likely ruled around 2500-2600 BCE. his version is not a mere transcription but a literary evolution, reshaping the tale from a heroic adventure into a philosophical quest for ancient wisdom. The added prologue and reflective tone shift the focus from conquest to introspection: the search for what is hidden, what is past. As professor Damrosch observed, even the oldest texts speak of antiquity as something already lost – suggesting that no one truly lives in antiquity, we live in the present, and always looking back.

Earlier fragments from the Old Babylonian period (circa 1600 BCE) reveal a more direct, action-driven narrative. But by the time of Sin-leqi-unninni’s compilation, the epic had matured into a masterpiece of world literature, layered with existential depth and poetic sophistication. As the saying goes, if it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a tradition to raise a masterpiece.

The text was written in Akkadian, specifically the Standard Babylonian dialect, on cuneiform clay tablets. Akkadian is a Semitic language, sharing linguistic roots with Hebrew and Arabic.

Akkadian language was lost for centuries and later deciphered. Its rediscovery and translation into modern languages made the epic accessible, but translation itself introduces creative shifts – sometimes expanding the meaning or casting the story in a new interpretive light. Each version reflects not only the original text but also the translator’s cultural lens.

The survival of this epic – through fragments, translation, and scholarly reconstruction – offers a rare glimpse into the literary soul of ancient Mesopotamia.

Famous figures in the rediscovery of the epic of Gilgamesh

Austen Henry Layard (1817-1894)

A British explorer and diplomat who, during travels through Turkey, Greece, and the Levant, heard rumors of mysterious mounds in what is now Iraq. In Mosul, he excavated the ruins of Nineveh, the ancient Assyrian capital, and uncovered the palace and library of King Ashurbanipal (Assur-Bani-Pal), known as the “King of the World.” Despite limited funding, Layard recovered over 100,000 clay tablets and fragments, many inscribed with cuneiform script, and shipped them to the British Museum. At the time, no one could read the tablets, but Layard believed scholars would eventually decipher them. He documented his discoveries in Nineveh and Its Remains (1849) and later published a bestselling follow-up, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon (1853). Layard later became a Member of Parliament, an expert on Assyrian culture, and a British ambassador.

Sir Henry Rawlinson (1810-1895)

A brilliant linguist and officer in Her Majesty’s service in Persia. Discovered the Behistun Inscription in western Iran- a trilingual text carved by Darius the Great – which became the Rosetta Stone for cuneiform. Spent two decades deciphering the scripts, eventually unlocking the ability to read Akkadian and other cuneiform languages. By the 1870s, scholars had a rudimentary grasp of cuneiform, thanks largely to Rawlinson’s work.

George Smith (1840-1876)

A self-taught scholar with no formal education, obsessed with biblical history. Worked at the British Museum, cleaning tablets from Layard’s collection. In his early 20s, discovered a tablet describing a flood narrative – a man in a boat sending out birds to check the waters – eerily similar to the story of Noah. This was the first deciphered portion of the Epic of Gilgamesh, and it caused a sensation. Published The Chaldean Account of Genesis (1876), which became a bestseller. Persuaded the British Museum to fund further excavations in Nineveh, where he found additional fragments of the flood story. Died tragically young at age 36, having written eight books and laid the foundation for modern Assyriology.

Literary stylistics of the epic of gilgamesh

The epic’s structure reflects ancient literary formality: it is dramatic, deliberate, and paced with a measured rhythm. Lines are often composed of half-lines arranged in couplets, creating a poetic cadence. In skilled hands, the second half-line builds on the first adding tension and depth. Techniques such as alliteration, repetition, and parallelism contribute to the dynamism of the text, making it feel alive and performative even across millennia.

The Epic of Gilgamesh operates on multiple scales typical of epic literature: a heroic quest, the foundation of a city, and the relationship between gods and humans. It is the largest known literary work from the ancient Near East, far surpassing earlier traditions of shorter poems. It incorporates older materials, such as the flood story, which was adapted from earlier texts and lightly revised – showing the epic’s engagement with it’s own textual history.

Though written on clay tablets, the epic was likely recited aloud, especially in courtly settings. It served both as entertainment and as a philosophical reflection on human nature, leadership, and mortality. The narrative allowed audiences to contemplate issues that could not be spoken openly – such as the flows of rulers – through the lens of myth.

The physical form of cuneiforms influenced the epic’s length and structure. Tablets were durable but heavy, and the epic’s twelve-tablet format reflects the practical limits of the medium. In the scribal culture of Assyria and Babylonia, literature coexisted with vast collections of omen texts, dream interpretations and ritual manuals. The epic emerged from this rich textual universe, shaped by both literary ambition and material constraints.

Gilgamesh’s development is not psychological in the modern sense; he doesn’t transform deeply as a personality but learns restraint and self-awareness. The epic often omits character motivation, as in the moment when Enkidu confronts Gilgamesh to stop him from violating a bride. The lack of explanation invites readers to project meaning, engaging them in active interpretation.

The epic blends comic and tragic elements. It ends where it began – Gilgamesh returns to Uruk, and the world remains unchanged. Yet he is sadder and wiser, having faced mortality and loss. The tragedy of Enkidu, who descends into chaos and dies cursed, contrasts with Gilgamesh’s return and reflection. The final scene where Gilgamesh admires the city walls and records his story, completes a comic arc of restoration, while preserving the tragic depth of human experience.

In a striking literary gesture, the epic closes with Gilgamesh writing down his story and burying it in the city wall – a symbolic act that makes him not only the first great hero of world literature, but also its first great author. As D. Damrosch notes, the epic is a meditation on memory, legacy, and the power of storytelling itself.

Gilgamesh: ambitions, power, landscape, and the tragedy of enkidu

The episode in which Gilgamesh and Enkidu leave the city to confront Humbaba is more than a heroic adventure – it’s a meditation on kingship, imperial ambition and the fragile balance between civilization and nature. Their journey into the Cedar Forest is not just mythic; it’s politically and environmentally charged.

In the ancient Near East, cities like Uruk were dependent on the countryside for resources – especially water and timber, both scarce and vital. The city and the land existed in a dialectical relationship: the city needed the rural population and natural world, but also sought to dominate and extract from it.

Gilgamesh, historically known for building city walls and digging irrigation wells, was figure of urban control and resource management. In fact, inscriptions from later centuries invoke his name when digging wells – ”Well of Gilgamesh’‘ – a testament of his enduring legacy as a master of infrastructure.

So when Gilgamesh sets out to cut cedar, it’s not a casual act – it signals imperial ambition. He’s extending his reach beyond the city, asserting dominance over nature, and violating the sacred forest guarded by Humbaba.

Gilgamesh’s behavior reflects unsustainable kingship:

- In the city, he abuses his subjects – violating social and moral boundaries.

- In the countryside, he violates the landscape, treating nature as something to be conquered rather than stewarded.

The killing of Humbaba is particularly telling. Though Humbaba is described as a mythic monster, his role resembles that of a rival chieftain – a guardian of a smaller polity. Gilgamesh and Enkidu negotiate with him, suggesting a moment of possible diplomacy. But they choose violence over alliance, eliminating a figure who could have become a subsidiary vassal, a sustainable source of tribute and stability.

This decision leads to Humbaba’s curse, which ultimately causes Enkidu’s death. The epic thus critiques rash leadership and the failure to balance power with wisdom.

Enkidu, once a wild man, becomes Gilgamesh’s companion and conscience. But in this episode, he fails to advise wisely. His support for the killing of Humbaba marks a turning point—not just in the plot, but in his own arc. The adventure of Gilgamesh becomes the tragedy of Enkidu, who pays the price for their shared hubris.

The epic operates as a political allegory, exploring the responsibilities of kingship in a world of limited resources and fragile alliances. Sîn-lēqi-unninni, the compiler of the Standard Babylonian version, weaves together multiple episodes—Ishtar’s rejection, Humbaba’s death—to create a synoptic tale of human ambition, divine justice, and the consequences of failed diplomacy.

Gilgamesh must learn that true leadership requires restraint, and that dominion over land and people must be tempered by wisdom, empathy, and sustainability.

Gilgamesh's rebellion and failed diplomacy

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the most startling episodes occurs when Gilgamesh rejects the goddess Ishtar, delivering a speech so aggressive and insulting that it defies the norms of divine-human relations. This act of rebellion is not just personal – it’s cosmic insubordination, and it triggers the gods’ decision to punish Gilgamesh by killing Enkidu, his beloved companion.

This moment is especially striking given the ideological framework of ancient kingship. In Mesopotamian court culture, the king was expected to be the servant, echo of the city’s patron deity. This relationship was not merely ceremonial – it was a sacred bond, a diplomatic and spiritual alignment that legitimized the king’s rule.

Ishtar, as the patron goddess of Uruk, represents that divine authority. Gilgamesh’s rejection of her is not just rash – it’s a failure of diplomacy, a refusal to mediate between his people and the divine hierarchy. His arrogance blinds him to the delicate balance required of a ruler. He sees himself as godlike, but he has not yet learned the restraint and reverence that true leadership demands.

Interestingly, the epic includes two major provocations that lead to Enkidu’s death: the insult to Ishtar and the slaying of Humbaba, the guardian of the Cedar Forest. Either one could have served the narrative purpose of divine punishment. The inclusion of both suggests that Sin-leqi-unninni, the compiler of the Standard Babylonian version, was crafting a synoptic tale – a layered exploration of human pride, divine justice, and the limits of power.

This dual structure allows the epic to probe tensions that could not be expressed directly in the court. Through myth, it critiques the dangers of unchecked authority and the consequences of ignoring sacred obligations. Gilgamesh’s journey is not just heroic – it’s educational. He must learn that power without humility leads to loss, and that true greatness lies in wisdom, not defiance.

A story within a story: the flood

The flood story appears late in the Epic of Gilgamesh, not as the central drama but as an interpolated tale – a story within the story. This technique reflects a long-standing tradition in Near Eastern literature of nested narratives, seen later in works like One Thousand and One Nights and even earlier in Egyptian texts. These embedded tales serve to expand the scope of the epic and deepen its philosophical resonance.

The inclusion of the flood story widens the lens of the narrative. While the epic begins with Gilgamesh’s personal journey – his friendship with Enkidu, his abuse of power, and his grief – it eventually scales up to the story of humanity itself. The flood tale, told by Utnapishtim, introduces themes of excess, destruction, and renewal, confronting Gilgamesh with the limits of human existence and the finality of death.

The flood story serves as a counterpoint to Enkidu’s arc. Enkidu begins the epic as a wild man, seduced into civilization—becoming human. Utnapishtim, by contrast, is a human who transcends mortality, becoming immortal after surviving the flood. These two figures frame Gilgamesh’s journey: one shows the entry into humanity, the other its limits and aspirations.

The flood story also reflects on the materiality of human life. Humans are made of clay, and so are their cities. A flood can wash away a baked clay city, just as death returns humans to dust. In this metaphor, the city becomes an extension of the hero’s body, a symbol of both permanence and fragility. Gilgamesh’s final act – admiring the walls of Uruk – underscores this connection between legacy and mortality.

Utnapishtim’s tale is sobering. He recounts how his patron god granted him immortality, but then tells Gilgamesh: “Who will do that for you?” The gods are real and powerful, but their world is not ours. Human contact with the divine is limited, and the House of Dust – akin to the Hebrew Sheol – is the fate that awaits all mortals. This moment marks a philosophical turning point: Gilgamesh must accept that immortality is no longer attainable.

The flood marks a boundary between myth and history. In ancient belief, the pre-flood world was one of mythic possibility – where kings lived for tens of thousands of years, and divine encounters were common. After the flood, the world becomes human, bounded by time, death, and limitation. Gilgamesh’s meeting with Utnapishtim is thus a meeting between eras: the historical king confronts the mythic survivor.

Gilgamesh returns to Uruk not with eternal life, but with understanding. He looks at the city walls – his creation – and finds meaning not in escaping death, but in leaving something behind.

- Stylistic tradition: Ancient Asian cultures favored nested storytelling, which explains the flood story’s placement.

- Mythic transition: The flood marks the shift from mythic immortality to human mortality, redefining the relationship between gods and humans.

- Philosophical framing: The flood story expands the epic’s scope from personal grief to universal human limits.

Corner stone of world literature

The epic encompasses the known world of its time, making it a work of world literature in an ancient context. It was widely circulated across Mesopotamia, Persia, Anatolia, and the Levant, and translated into multiple languages over centuries.

The epic explores eternal human concerns: power and its abuse, diplomacy and its absence, mortality, friendship, and the tension between civilization and nature. It is politically charged, yet presented in a mythic and poetic form suitable for courtly performance, allowing sensitive critiques of leadership to be voiced safely. Gilgamesh’s journey reflects the struggles of rulers, the consequences of arrogance, and the need for restraint and wisdom.

Enkidu, the wild man, mirrors Gilgamesh: just as Gilgamesh disrupts the city, Enkidu disrupts the countryside. Their relationship dramatizes the conflict between nature and civilization, and the need for balance between power and humility.

Though written, the epic was recited aloud, especially in royal courts, serving as both entertainment and philosophical reflection. It allowed audiences to contemplate issues of governance and morality that could not be spoken openly.

Gilgamesh is often called the original myth, a foundational narrative that shaped later storytelling traditions. It blends mythic grandeur with realistic psychology, making it both timeless and deeply human.

Ancient Near Eastern literature often used stories within stories to create layered, expansive narratives. Even ancient writers were writing about their own antiquity, using myth to conceal hard truths and navigate political sensitivities. Approaching the epic through socio-cultural, political, and agricultural lenses revealed new dimensions beyond its mythic surface. The translation lacked poetic rhythm, but analysis revealed the story’s philosophical richness, transforming indifference into appreciation. Literature in ancient Mesopotamia was deeply tied to urban power structures – written in cities, for courts, temples, and merchants, serving economic, imperial, and religious interests.

Motifs, absences and interpretation

One of the most striking aspects of The Epic of Gilgamesh is how it balances political complexity with narrative openness. Gilgamesh begins as an autocratic ruler, abusing his power while his people cry out to the gods for help. In ancient chronicles – Babylonian, Egyptian, Assyrian – the king and his counselors typically know the story they’re in. Wisdom is shown through foresight. But in Gilgamesh, the protagonist is surprised, confused, and flawed, making the epic feel more human, more real.

The epic gives clear motivation to Enkidu when he confronts Gilgamesh for raping a bride – he acts as a moral counterweight. But later, when Enkidu persuades Gilgamesh to kill Humbaba, defying the god Shamash’s warning, the text offers no explanation. This absence is not a flaw – it’s a deliberate blank space, inviting readers to project their own interpretations.

Like visual art, literature does not always carry fixed meanings. Instead, it lives in the mind of the reader. The more one returns to the same story, the less one is impressed by its surface, and the more one is drawn into its depths. Each reading becomes a personal encounter, shaped by one’s own inner world – kokijan ymmärrykset ja tulkinnat, unique and intimate.

Books and compositions exist most fully in the consciousness of their audience. The epic’s silences – its lack of psychological explanation, its mythic gaps – are not limitations but openings. They allow the reader to become a co-creator of meaning.

Professors Puchner and Damrosch approach Gilgamesh from many directions:

- As a political allegory, exploring power dynamics, abuse, and the tension between ruler and ruled.

- As a mythic narrative, where Gilgamesh and Enkidu mirror each other – one disrupting the city, the other the countryside.

- As a philosophical journey, where Gilgamesh seeks not just immortality for himself, but for his people: “I will bring the flower and give it to my nation.”

This quest reveals Gilgamesh as sensitive, emotional, and brave – a hero who refuses to accept the limits of mortality. His journey to the underworld is not just mythic – it’s existential. The epic becomes an ode to mortality, expressing a longing that ancient people – whether in 22nd or 7th century BCE – shared: the desire to transcend death, to preserve meaning, to live forever.

In its courtly setting, the epic served as a safe space for dangerous truths. Through myth and poetry, it raised questions that could not be asked directly: What happens when a ruler goes off the rails? How should power be restrained? What does it mean to be human?

By embedding these questions in epic form, the text became diplomatic, layered, and timeless. It allowed critique without confrontation, reflection without rebellion.

Conclusion: a living masterpiece

The Epic of Gilgamesh is not just the oldest surviving literary work – it is a living masterpiece. Its motifs, absences, and ambiguities invite endless interpretation. It speaks to universal human concerns – power, mortality, friendship, and the search for meaning. And it reminds us that literature, like all great art, is not just what is written – it is what is felt, imagined, and understood by each reader.

So, this week’s world literature piece not only introduced me to the realm of ancient mythology and its rich cultural atmosphere, but also prompted deep self-reflection. It made me examine my internal world – my values, boundaries, and the ways I respond to challenging material. Literature, I’ve discovered, doesn’t just open windows into other civilizations; it also holds up a mirror to our own.

Study pace reflection

This week’s material included a one-hour lecture, a test, and a reading assignment focused on The Epic of Gilgamesh. A surface-level reading and simply attending the lecture would have been enough to pass the test. However, because I wanted to document the process and truly engage with the material, I chose to go further—structuring my learning more intentionally.

After listening to the lecture, I took time to sit quietly and reflect. I recalled the key points, the questions raised, and the themes that resonated with me. I wrote down the chapters and ideas I wanted to explore in my diary. I also asked myself what I hadn’t fully understood, and identified areas where I needed more clarity.

To find answers, I returned to the lecture, revisiting the texts and discussions. I extracted relevant passages, worked with them closely, and added insights to my draft. This process helped me fill in the gaps, deepen my understanding, and shape a more complete reflection.

By choosing to go beyond the minimum, I transformed a simple assignment into a meaningful learning experience. It was not just about passing a test—it was about building knowledge, asking questions, and connecting with the material in a personal and thoughtful way.