Why Conflicts Arise More Often and How to Prevent Them

Intercultural creative projects are becoming increasingly common. They bring together people with different cultural codes, aesthetic traditions, and levels of professional experience. Yet these teams also face a higher risk of conflict. Research shows that intercultural creative groups are particularly vulnerable to tension, misunderstanding, and power struggles.

Below is a research‑based overview of the key mechanisms that influence the success of intercultural creative teams — and the strategies that help them thrive.

Blurred Roles Intensify Conflict

Creative teams often strive for horizontal structures and avoid rigid hierarchy. However, studies in team dynamics show that when roles are unclear, teams remain stuck in the storming phase — characterized by competition, power struggles, and interpersonal conflict (Tuckman, 1965).

This is especially visible in creative projects because:

- there is no formal hierarchy,

- decisions are made intuitively,

participants interpret leadership differently.

Kozlowski & Ilgen (2006) confirm that role ambiguity is one of the strongest predictors of conflict in teams.

Psychological Safety Is the Foundation of Creativity

Amy Edmondson (1999) demonstrated that psychological safety — the ability to share ideas without fear of ridicule — directly affects team performance.

In creative work, this is crucial because:

- ideas are often unpolished,

- participants feel vulnerable,

criticism is easily taken personally.

Non‑constructive comments (“ugly”, “stupid”) undermine trust and reduce willingness to collaborate. Bandura (1997) notes that negative personal evaluations decrease self‑efficacy and harm performance.

Cultural Essentialism Blocks Dialogue

Intercultural teams often encounter cultural essentialism — the belief that culture is fixed, uniform, and unquestionable (Holliday, 2011).

This leads to:

- using culture as a tool of pressure,

- shutting down creative discussion,

- limiting artistic freedom,

- escalating conflict.

Hofstede’s model (2001) also shows that differences in power distance and collectivism can intensify misunderstandings when participants hold different cultural expectations about leadership and collaboration.

Psychological Types Amplify Tension

Research in group dynamics (Forsyth, 2014) shows that certain personality combinations make teams more vulnerable to conflict.

The anxious type: Clark & Beck (2010) describe anxious individuals as prone to:

- catastrophizing

- discomfort with uncertainty,

negative reactions to unfamiliar cultural elements.

The aggressive-impulsive type: Gross (2015) links impulsive aggression to:

- low emotional regulation,

- a desire for dominance,

using pressure as a control strategy.

Destructive coalition: Forsyth (2014) identifies a pattern where:

- the anxious member amplifies the aggressive one,

- the aggressive member provides “protection”,

tension is redirected toward a third party or the leader.

Amateur Teams and the Problem of Binary Judgments

Creative projects often include participants with varying levels of training. Amateurs who lack a professional artistic vocabulary tend to rely on binary categories:

- “beautiful / ugly”,

- “right / wrong”,

“I like it / I don’t like it”.

Sawyer (2012) notes that without skills in analysis, composition, or cultural interpretation, amateurs respond emotionally to complex artistic decisions.

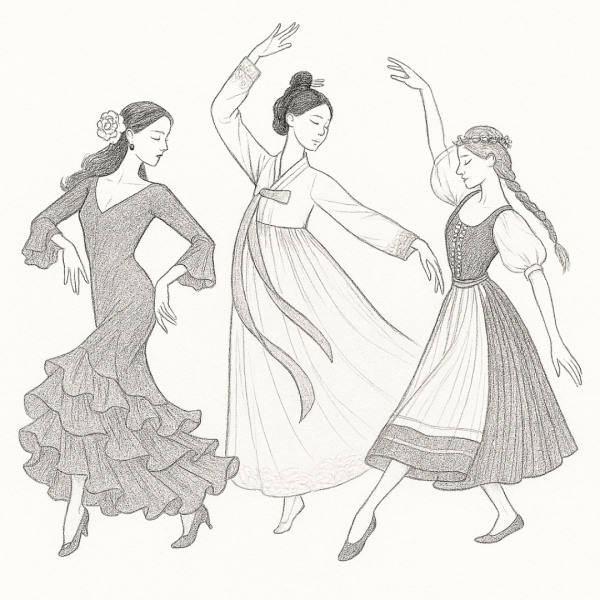

This becomes especially problematic in intercultural projects, where gestures and symbols may carry deep cultural meaning.

Why Manipulation Is Common in Creative Teams

Research identifies several structural reasons why creative groups are more prone to manipulation:

- Informal structure: Flexible teams without clear hierarchy are more vulnerable to hidden power struggles (Hargadon & Bechky, 2006).

- Subjectivity of artistic evaluation: Amabile (1996) shows that subjectivity makes participants more vulnerable to manipulative criticism.

- Emotional involvement: Bohm (1998) emphasizes that creativity heightens emotional sensitivity.

- Leadership vacuum: Hogg (2001) describes how reluctance to lead creates space for informal leaders — often the most dominant or aggressive individuals.

- Competition for stage visibility: Bennett (2009) notes that the stage is a limited resource, intensifying competition for status.

Cultural Competence as a Key Resource

Cultural competence — the ability to understand and interpret cultural symbols — is essential in intercultural projects (Byram, 1997; Deardorff, 2006).

Its absence leads to:

- misinterpretations,

- devaluation of traditions,

- emotional conflict,

- reduced artistic quality.

Spitzberg & Changnon (2009) show that low cultural competence correlates with anxiety and negative reactions to unfamiliar practices.

How to Strengthen Intercultural Creative Projects

1. Formalize the Structure

- define leadership,

- establish decision‑making rules.

2. Build Psychological Safety

- discourage derogatory comments,

- encourage respectful communication.

3. Develop Cultural Competence

- explain symbolism,

- discuss cultural differences openly.

4. Manage Emotional Dynamics

- prevent aggression,

- support constructive dialogue.

5. Distinguish Cultural Dialogue from Cultural Manipulation

- avoid essentialism,

- promote mutual learning.

Conclusion

Intercultural creative projects require clear structure, defined roles, and strong intercultural communication skills. Conflicts in such teams often arise at the intersection of cultural differences, psychological factors, and variations in professional experience.

Understanding these mechanisms — and grounding practice in research — enables the creation of more resilient, mature, and productive creative teams capable of genuine intercultural collaboration.

Sources

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context. Westview Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429501234

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3742605

Barker, J. R. (1993). Tightening the iron cage: Concertive control in self‑managing teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38(3), 408–437. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2393374?origin=crossref

Bennett, D. (2009). Academy and the real world: Developing realistic curricula for highly specialized music degree programs. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 8(3), 297–307.

Bohm, D. (1996). On dialogue. Routledge.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters. https://dokumen.pub/teaching-and-assessing-intercultural-communicative-competence-revisited-9781800410251.html

Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (2010). Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: Science and practice. Guilford Press.

De Dreu, C. K. W., & Weingart, L. R. (2003). Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: A meta‑analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 741–749. DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.741

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306287002

Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict: Constructive and destructive processes. Yale University Press.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2666999?origin=JSTOR-pdf

Forsyth, D. R. (2014). Group dynamics (6th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Hargadon, A., & Bechky, B. A. (2006). When collections of creatives become creative: A field study of problem solving at work. Organization Science, 17(4), 484–500. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0200

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00184-5

Holliday, A. (2011). Intercultural communication and ideology. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446269107

Hogg, M. A. (2001). A social identity theory of leadership. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(3), 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0503_1

Jehn, K. A. (1995). A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(2), 256–282. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393638

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Ilgen, D. R. (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(3), 77–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00030.x

London, M. (2003). Job feedback: Giving, seeking, and using feedback for performance improvement. Psychology Press. DOI:10.2307/20159059

Mumford, M. D., Connelly, M. S., & Gaddis, B. H. (2003). Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(3), 273–307. DOI:10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00041-7

Paulus, P. B., & Nijstad, B. A. (Eds.). (2003). Group creativity: Innovation through collaboration. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195147308.001.0001

Sawyer, R. K. (2012). Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). Jossey‑Bass.

Spitzberg, B. H., & Changnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 2–52). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071872987.n1

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100