Poetry, history, politics, religion, aesthetics – written by women

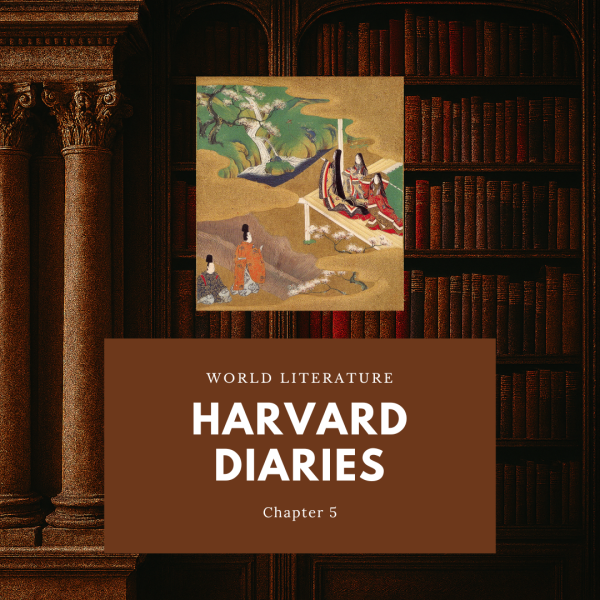

This week’s literary piece at Harvard is The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu, often considered one of the greatest works of world literature — and perhaps the most significant work ever written by a woman before the modern age. Composed over 1,000 years ago in Japan, it presents a world that feels both immediate and remarkably different from our own. The setting is the highly ritualized court society of 11th‑century Japan, governed by explicit and implicit rules that are unfamiliar to modern readers.

Because the book is vast — spanning multiple sections, each over 800 pages — professors assigned only selected chapters.

- I. The Lady of the Paulownia–Courtyard Chambers. Introduces Genji’s mother, Lady Kiritsubo, and her tragic fate. Sets up Genji’s origins, his ambiguous status, and the theme of courtly jealousy.

- II. Broom Cypress. Genji’s early romances and the famous “ideal woman” discussion among courtiers. Establishes the rules of love and rank, and introduces Murasaki (the heroine).

- V. Little Purple Gromwell. Genji meets young Murasaki, whom he raises to become his ideal partner. Raises ethical questions about grooming, love, and the tension between rules and passion.

- VII. An Imperial Celebration of Autumn Foliage. Courtly rituals and seasonal aesthetics; Genji shines socially.Shows the importance of ceremony, beauty, and reputation in Heian society.

- IX. Leaves of Wild Ginger. Romantic entanglements and gossip intensify. Illustrates repetition of scenarios and the floating narrative style.

- XII. Exile to Suma. Genji is banished after scandal. A turning point: exile highlights impermanence, vulnerability, and the fragility of status.

- XIII. The Lady at Akashi. Genji’s romance with the Akashi Lady, leading to the birth of a daughter. Introduces destiny and lineage — the daughter will later marry into the imperial line.

- XXV. Fireflies. A famous scene where Genji uses fireflies to reveal hidden beauty. Symbolic of illumination, fleeting beauty, and the art of courtly display.

- XL. The Rites. Rituals and ceremonies dominate; Genji’s later life is marked by reflection. Shows the weight of tradition, the limits of passion, and the inevitability of decline.

This selection of chapters describe the arc of Genji’s rise, fall, exile, and return, while also showcasing the aesthetic rituals and emotional subtleties that make the novel unique. Traditionally, readers in Japan did not approach The Tale of Genji as a continuous novel. Instead, they read chapters individually, often focusing on the poems within them. The text is episodic, resembling The 1,001 Nights: chapters are semi‑self‑contained, sometimes separated by years, with transitions that leave gaps in the narrative. Events may be revealed only later, casually inserted into another episode.

What follows are my notes and reflections from the lecture, held by Martin Puchner, David Damrosch and Wiebke Denecke. A personal record of how this masterpiece of world literature continues to shape our understanding of poetry, history, politics and aesthetics.

A World both distant and familiar

The Tale of Genji is compelling because of its dual nature. On one hand, it is an insular work, deeply rooted in the rituals, hierarchies, and aesthetics of medieval Japanese court life. On the other, its exploration of desire, frustration, and emotional nuance resonates across time and cultures. At the heart of the narrative lies a tension between social rules and human passion. Readers are invited to ask: What is permitted? What is frowned upon? What is impossible? Murasaki Shikibu probes these boundaries through increasingly daring transgressions, especially in matters of romance. Gossip replaces the narrator’s voice, showing how society itself enforces rules while individuals test their limits.

Genji himself embodies this tension. As the son of a consort of lower rank, he is destined for greatness but barred from becoming emperor. The very term genji refers to someone of imperial lineage who is made into a commoner to avoid political danger. This makes Genji both privileged and precarious — a perfect man who cannot rule, much like Achilles in The Iliad, who surpasses Agamemnon yet lacks the rightful position. The author, known by the appellation “Murasaki Shikibu,” was named after her heroine Murasaki, a woman of middle rank — neither too high nor too low, which was considered ideal in courtly romance. In this society, marriage was largely political, arranged to secure alliances, while romantic relationships existed outside of marriage. Against this rigid backdrop, the novel offers brief but vivid portraits of emotion and psychological depth that feels strikingly modern.

Court life, transparency, and the floating narrative

The novel also immerses readers in the atmosphere of Heian court life, where architecture itself reflected social dynamics. Houses were so open that privacy was minimal; conversations could be overheard in adjoining rooms, and gossip circulated constantly. This culture of surveillance and judgment shapes the narrative, where characters are always aware of how they are perceived. The abundance of characters can be confusing, which is why some translations include lists to help readers keep track.

Another unusual feature is the repetition of scenarios: similar situations recur again and again, but with different combinations of people. This creates a “floating narrative,” echoing the Japanese artistic theme of ukiyo‑e (“Floating World”). Instead of progressing in a straightforward way, the story cycles through variations and obsessions, gradually teaching readers the rules of its society. In this way, The Tale of Genji becomes both a reflection of its own world and a timeless meditation on the interplay between rules, passion, and human emotion.

From Japan to Europe: Circulation and artistic influence

For centuries, The Tale of Genji circulated within Japan, primarily through court circles and later via inexpensive woodblock prints. These illustrated editions, often beautifully crafted, allowed the text to reach wider audiences, though it remained largely unknown outside Japan until the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

This delay coincided with Europe’s fascination with Asian art and culture, a trend known as chinoiserie and later Japonaiserie. As European artists grew weary of realism, they sought inspiration in stylized, abstract forms from China and Japan. Japanese woodblock printing, developed to its highest level in East Asia, became especially influential. Multi‑colored prints required master outline blocks and multiple color blocks, each pressed in sequence to create vibrant images. Though considered popular art in Japan — affordable alternatives to painting — these prints captivated Europeans, who admired the idea of a culture where everything, from chopsticks to poetry, was part of a unified artistic system. Screens depicting Genji scenes further piqued curiosity, prompting Europeans to ask: what were these stories about?

Translating Genji: Waley, Seidensticker, and Tyler

The first English translation appeared between 1925 and 1933, produced by Arthur Waley. His Genji was a tremendous success, but highly idealized. He omitted entire chapters and excluded the poetry — despite the fact that Murasaki Shikibu was one of the great poets of her era, with nearly 800 poems woven into the narrative. For medieval and early modern audiences, the poems were the centerpiece, with the prose serving as a frame to contextualize them. Murasaki’s readers understood the story as existing for the sake of the poems. The brevity of the verses, their refinement, and their emotional resonance gave Genji its distinctive rhythm — a massive text punctuated by moments of lyrical intensity.

This contrasts sharply with Arthur Waley’s early English translation, which treated the poems as interruptions to the story. Waley’s version read like a fairy tale for Edwardian aesthetes, even opening with a French epigraph from Charles Perrault’s Cinderella.

Later translators sought greater accuracy. In the 1970s, Edward Seidensticker, a scholar of modern Japanese literature, produced a spare, modernist version. His translations of the poems resembled concise couplets, cool and ironic in tone, accompanied by extensive footnotes to explain cultural context. Most recently, Royall Tyler’s 2001 abridged edition offered the most detailed immersion into Heian court life. A specialist in medieval Japan, Tyler provided long appendices and three times as many footnotes, carefully explaining hierarchies, rituals, and settings. His style is warmer, positioned between Waley’s romanticism and Seidensticker’s modernism, but always attentive to the text’s cultural depth.

Poetry, calligraphy, and courtly refinement

In The Tale of Genji, characters live within a world so restricted by rules and regulations that their primary mode of communication is poetry. This is one of the novel’s most remarkable features, reflecting the aesthetic values of Heian Japan. Poetry was not only a form of art but also a social necessity: every educated person was expected to compose poems daily, and true refinement was measured by the quality of one’s verse and calligraphy. A hero or heroine’s skill in poetry revealed both education and character.

Murasaki Shikibu herself mastered Chinese, even teaching it secretly to the Empress, though vernacular Japanese prose and poetry were considered less prestigious than Chinese forms. Against the grandeur of China, Japan cultivated an aesthetic of spareness and elegant restraint. Poems could hint at feelings through allusion, seasonal references, or subtle calligraphic choices. The paper, ink, and even perfume used carried meaning. Women were expected to write lightly, with suggestion rather than boldness, while ostentatious refinement — such as overusing Chinese characters — was frowned upon.

Genji’s relationships often unfold through poetic exchanges: a poem and its answering poem, sometimes improvised on the spot, sometimes carefully delayed, much like the timing of modern text messages. Waka poems, fixed at five lines and 31 syllables (5–7–5–7–7), demanded creativity within strict rules. This restraint was prized, and later evolved into the even shorter haiku form (5–7–5). Thus, poetry in Genji is not an interruption but the very heart of communication, embodying refinement, emotion, and social negotiation.

Differences and similarities to the modern novel

Unlike most modern novels, The tale of Genji does not follow a tightly structured plot with a clear beginning, middle, and end. The hero dies two‑thirds of the way through, yet the narrative continues for hundreds of pages, shifting to the next generations. The ending itself is ambiguous. This open‑endedness reflects a broader Japanese aesthetic, later embraced by writers such as Higuchi Ichiyō in the 1890s, and resonates with modernist techniques that favor unresolved narratives.

The novel is also not driven by plot in the conventional sense. What matters is not the sequence of events but how actions are reflected within the characters — their emotions, their fleeting attachments, their poetic exchanges. In this way, Genji anticipates the psychological novel, where interiority and reflection outweigh external action. Genji is not about suspense or resolution but about the texture of experience, the evanescence of beauty, and the subtle interplay of rules and passion.

Despite these differences, The Tale of Genji shares important qualities with the modern novel. It is a continuous prose narrative of considerable length, populated by complex characters whose inner lives are explored with remarkable psychological depth. Its episodic structure, while unusual, still builds a coherent world across generations. The emphasis on character development, emotional nuance, and social context aligns it with later traditions of the psychological and realist novel.

What makes Genji especially compelling is its ability to feel modern despite its age. The open ending invites readers to reflect rather than to seek closure. The narrative lingers on poetic moments and emotional subtleties, creating a rhythm that resonates with contemporary readers accustomed to fragmented, introspective storytelling. At the same time, the cultural shocks within the text — what was scandalous in Heian Japan but not to us — remind us of the historical distance. Thus, Genji stands both as a precursor to the novel and as a unique form that challenges our assumptions about what a novel should be.

The beauty of evanescence

Romance in Genji is treated as a high art, from the elegance of leave‑taking to the refinement of poetic exchanges. Yet as the story progresses, these perfect romances take on a darker tone. The deaths of Murasaki and Genji mark a shift toward the aesthetics of impermanence. Murasaki’s passing is accompanied by the haunting line: “Grief does not correspond to love. The love will be shorter, the grief will be longer.” Genji’s death is captured with equal poignancy: “Bright spring was dark that year.”

These lines are shocking in the Japanese context, where the natural order — symbolized by the seasons and their predictable cycles of flowers, moods, and poems — was seen as the foundation of life. To say that spring was dark is to suggest that the world itself has broken down. In this way, The Tale of Genji pushes beyond romance and ritual to confront the limits of human happiness. It embodies the Heian aesthetic of mono no aware — the awareness of life’s transience — reminding readers that beauty and love are fleeting, and grief endures longer than joy.

Chinese influences and Japanese distinctiveness: waka and vernacular aesthetics

Although The Tale of Genji is celebrated as Japan’s national classic, its Chinese influences are undeniable, even if often overlooked or downplayed in modern times. Chinese texts serve as master references within the novel, most notably Bai Juyi’s Song of Everlasting Sorrow, which tells of an emperor mourning his beloved concubine. This theme of impossible, transcendent love runs like a red thread through Genji. Murasaki Shikibu herself taught Bai Juyi’s works to the empress, underscoring how deeply Chinese literature shaped her imagination.

China also appears as a source of authority and cultural prestige. Early in the novel, Genji’s fate is predicted by diviners from Korea and China, whose continental knowledge carried weight in Heian Japan. Later, during Genji’s exile, he builds a hut modeled on Bai Juyi’s own retreat, and the chapters are filled with references to Chinese works and poets. Exile becomes a space imagined as halfway between China and Japan — geographically Japanese, but literarily tinged with Chinese associations. In this way, Genji situates itself within a broader East Asian cultural sphere, even while asserting its Japanese identity.

At the same time, Murasaki Shikibu’s work embodies a distinctly Japanese aesthetic. In the Heian period, women were not permitted to write in Chinese, much as European aristocratic women were discouraged from writing in Latin. Murasaki, highly educated through her brother’s tutors, knew the Chinese classics but could not incorporate Chinese poetry directly. Instead, she filled Genji with waka — short vernacular poems of 31 syllables (5–7–5–7–7). These 795 poems form the communicative web of the novel, shaping relationships and emotional exchanges.

Waka differ from Chinese verse in both form and sensibility. Chinese poems often consist of eight regulated lines, with dense meaning packed into monosyllabic words. Japanese, by contrast, is agglutinative, producing longer words and inflected verbs, so its poetry emphasizes suggestion and atmosphere rather than density. Place names, plants, and seasonal references carry symbolic weight: characters themselves are named after flowers or colors, such as Murasaki (purple gromwell) or Kobai (red plum). This shorthand code of associations creates a highly suggestive, indirect style.

Thematically, Japanese poetry also diverges. Chinese verse often celebrates liquor, music, and male camaraderie, while love is rarely central. In Heian Japan, however, love and longing were primary subjects, expressed through refined, indirect imagery. Thus, even if Murasaki had written in Chinese, the register would not have suited her themes. By choosing waka, she aligned her work with Japanese sensibilities of restraint, elegance, and emotional subtlety.

Women's power, vulnerability and space in the tale of Genji

Murasaki Shikibu registers women’s experience with striking ambivalence: in some sense, they are powerful, yet in another, they are pawns in a patriarchal system. The Tale of Genji, often called the first novel of world literature, was written by a woman in a society where female authorship was unusual but not isolated. Heian Japan witnessed a flourishing of women’s writing — monogatari tales and nikki diaries — in which court ladies recorded personal experiences, disappointments, and romantic entanglements. This literary phenomenon was tied to political structures: women like Murasaki and Sei Shōnagon served as ladies‑in‑waiting to Fujiwara daughters, who were offered to the emperor to secure power for their clan. Educated and refined, these women wrote from within the system, their voices both enabled and constrained by it.

Within the novel, romance is largely male‑dominated. Aristocratic men, including Genji, move freely among lovers, while women wait behind blinds, unable to initiate encounters. At times, Murasaki’s narrator bursts in with outrage, exposing Genji’s promiscuity and hypocrisy. At other times, she yields to his aura of transcendental beauty, presenting him as irresistible. This tension makes the novel compelling: women are often passive or marginalized, as in the case of the Akashi Lady, whose daughter becomes empress but who herself remains sidelined. Yet the narrative also acknowledges women’s losses, frustrations, and quiet resilience, registering inequality while still being drawn to Genji’s brilliance.

Equally fascinating is how Genji constructs women’s spaces. The novel unfolds in a capacious world that includes the court, the provinces, and the unseen interiors of aristocratic houses. These spaces are bounded by paper walls and symbolic “glass ceilings,” reflecting the limits placed on women. Murasaki herself could not compose in Chinese, nor enter certain male domains, yet as narrator she inhabits the male gaze, observing women from outside and imagining spaces she could not physically enter. This act of imaginative projection is itself radical: she moves beyond the diary tradition, where women wrote from behind blinds, into fiction that envisions perspectives otherwise inaccessible.

In this sense, Genji is not fiction in the Platonic sense of falsehood versus truth, but rather a poiesis — a creative imagining of spaces and experiences. Murasaki Shikibu uses her narrative voice to explore the boundaries of women’s lives, sometimes bracing against them, sometimes acknowledging she cannot go further. The novel becomes a capacious room of gazes: men looking at women, women looking at men, and the narrator herself looking at the entire system. Through this interplay, Genji registers both the constraints and the possibilities of women’s experience, making it a foundational text not only for Japanese literature but for world literature as a whole.

The origins of Genji

Japan imported many Chinese literary genres, but the one form absent in China at the time was the long prose novel. Vernacular prose writing in Japan only began around 905, with the imperial anthology of waka poetry (Kokinshū), whose preface was written in Japanese rather than Chinese. Developing prose was difficult, given the complexities of honorifics and social hierarchies embedded in the language. Yet within a century, Murasaki Shikibu achieved extraordinary sophistication, producing a continuous prose narrative of unprecedented length and depth.

Before Genji, Japanese prose existed mainly in shorter episodic tales, or monogatari. The most important precursor was The Tales of Ise, centered on the historical figure Ariwara no Narihira, a celebrated lover. These works were episodic collections of romantic anecdotes rather than sustained narratives. Murasaki built on this tradition but transformed it: she wove episodes into a larger structure, binding them together through repetition, variation, and thematic echoes.

The composition of Genji likely retained elements of oral storytelling — episodes told by the brazier on cold evenings — but Murasaki elevated this mode into a complex literary architecture. Genji’s repeated attempts to replace his lost mother with different women, and later the descendants who replay, twist, or fail to replicate his experiences, create a structuralist tableau of variations. The novel achieves a depth of patterning and interconnection that had not existed before. In this way, The Tale of Genji stands as both a continuation of earlier episodic traditions and a radical innovation: the first fully realized long prose novel in world literature.

The provenance of the Japanese tale (monogatari) and novel genre lies in historiography. In China, official histories such as the Spring and Autumn Annals and Sima Qian’s Records of the Historian chronicled dynastic events, emperors, jealous empresses, and biographies of notable figures. Japan adopted this model, appointing court officials to compile histories during the early Heian period. Against this backdrop, The Tale of Genji positions itself as both a continuation and a challenge to historiography.

A telling moment occurs when Genji scolds Tamakazura for reading tales, dismissing them as “lies.” She retorts that he himself is the liar, and the conversation shifts to the idea that tales fill in what histories leave out. Histories provide fragmentary records of reigns and political events, while tales capture private experiences, emotions, and the subtleties of courtly life. In this sense, Genji functions as a semi‑historical novel: its opening situates the story in “a certain reign,” echoing the formula of Chinese chronicles, yet deliberately avoids fixing the time. The novel acknowledges historical frameworks but resists being bound by them, creating a space where fiction can imagine what official records omit.

Although Genji is deeply invested in private experience, it also reflects the political structures of its time. Genji’s father is modeled on the Daigo Emperor, under whom the first vernacular waka anthology was compiled. Genji’s exile parallels the fate of Minamoto no Takaakira, banished by the Murakami Emperor. These historical echoes anchor the narrative in recognizable political contexts, even as Murasaki invents freely.

The novel also dramatizes the regency system dominated by the Fujiwara clan. Genji’s closest friend, Tō no Chūjō, belongs to this family, which monopolized power by marrying daughters into the imperial line. The Fujiwara held the post of Minister of the Left, the most powerful position beneath the emperor, while rival factions such as the Kokiden lineage controlled the Minister of the Right. Genji’s affair with a Kokiden woman reserved for the crown prince leads to his exile, underscoring the dangers of crossing factional lines.

Through these episodes, Genji offers subtle commentary on Fujiwara dominance. The Sugawara family’s scholar Minamoto no Takaakira, exiled in 901, represents the last non‑Fujiwara figure to reach high office before the clan’s monopoly. Murasaki’s narrative reflects the anxieties of other aristocratic families, showing how power was consolidated, manipulated, and sometimes abused. While not overtly critical, the novel reveals the political undercurrents of Heian society, blending romance and private life with the realities of court competition.

Buddhism as Cultural background, exit strategy, and philosophy in the Uji Chapters

The Tale of Genji is Buddhist in a cultural sense: it reflects the world Murasaki Shikibu inhabited, where Pure Land Buddhism was pervasive. Pure Land practice emphasized devotion to Amitābha (Amida), promising rebirth in the Pure Land as an intermediary step toward enlightenment. Acts such as copying sutras, making pilgrimages, and performing rituals were central, and these practices appear throughout the novel. Pilgrimages, in particular, offered women rare opportunities to leave the confines of court life and encounter the wider world.

Religion also functions as an “exit strategy.” When characters are overwhelmed by shame, jealousy, or grief, they turn to Buddhist renunciation. The Third Princess, mortified after her affair with Kashiwagi, immediately becomes a nun. Murasaki herself longs to take vows as she grows weaker, but Genji resists, deferring her renunciation until her deathbed. The cutting of hair — the ritual act of becoming a nun — is performed too late to benefit her, dramatizing the pain of delayed salvation. In this way, Buddhism provides a cultural and narrative framework for withdrawal from worldly suffering, even if imperfectly realized.

In the final third of the novel, the Uji chapters, Buddhism becomes more explicitly philosophical. Themes of impermanence (mujō) and unfulfilled desire dominate. Mahāyāna Buddhism, which shaped East Asia, emphasized salvation through compassion and engagement with the world, not just solitary asceticism. In Genji, this is reflected in scenes where desire remains unsatisfied: men lie beside women without consummation, attachments linger unresolved, and longing itself becomes a form of suffering. These depictions resonate with Buddhist ideas that worldly attachments cannot bring lasting fulfillment.

The novel also reflects the spectrum of Buddhist practice in Heian Japan. Aristocratic temples such as Kinkaku‑ji embodied contemplative refinement, while popular sites like Kiyomizu‑dera offered performative rituals — ringing bells, pouring water, joining crowds. Hermitage traditions appear too: Genji’s younger brother retreats to Uji, embodying the figure of the courtly hermit who withdraws yet still participates in poetry and culture. This duality — withdrawal and engagement — anticipates medieval Japanese traditions where poets lived in solitude but remained tied to courtly aesthetics.

Conclusion

The Tale of Genji stands at the crossroads of poetry, history, politics, religion, and aesthetics. It is at once a historical novel, a poetic anthology, a meditation on impermanence, and a subtle commentary on power. Murasaki Shikibu drew on Chinese models yet created something distinctly Japanese, weaving waka poetry, courtly rituals, and Buddhist sensibilities into a narrative of extraordinary depth.

What makes Genji timeless is its ability to hold contradictions: women are both powerful and constrained; romance is both refined and destructive; poetry is both communication and art; religion is both cultural background and existential escape. The novel is episodic yet coherent, deeply psychological yet socially embedded, rooted in its time yet astonishingly modern in its open‑endedness.

As the first long prose narrative in world literature, written by a woman in a patriarchal court, Genji is more than Japan’s national classic. It is a work that redefines what fiction can do: filling in what history leaves out, imagining spaces otherwise inaccessible, and capturing the fleeting beauty of human experience. Its enduring power lies in its evocation of mono no aware — the awareness of life’s transience — reminding us that love, grief, and longing are inseparable, and that even “bright spring can be dark.”