A Literary Odyssey Across Cultures

This week at Harvard, I’ve been immersed in The Thousand and One Nights—a text that continues to surprise me with its complexity, adaptability, and global reach. Under the guidance of Professors Martin Puchner, Paolo Horta, Sandra Naddaff, and David Damrosch, we’ve explored the Nights through diverse, deeply researched, and often enchanting materials. Each discussion opened new doors into the text’s layered history, its cultural transformations, and its literary legacy.

What follows are my notes and reflections from the week—a personal record of how this ancient collection of stories continues to shape our understanding of storytelling, translation, and world literature.

Introduction

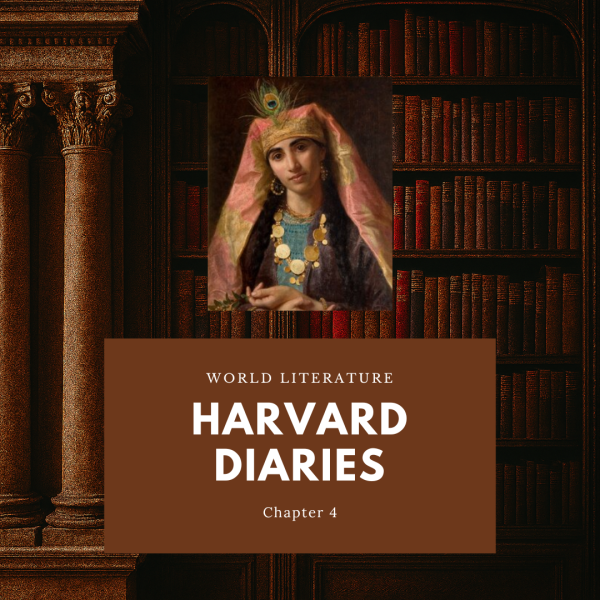

The Arabian Nights, also known as One Thousand and One Nights, or Alf Layla wa Layla, is one of the most iconic examples of frame-tale literature—a genre where a central narrative contains many embedded stories. It became literature through centuries of transformation. Its origins are rooted in oral storytelling, and its evolution reflects a rich tapestry of cultural exchange, adaptation, and reinterpretation. Though its roots span Persian, Indian, and Arabic traditions, the figure of Scheherazade stands out as the most celebrated storyteller in world literature.

At the heart of The Arabian Nights lies a political and moral crisis. The story begins with a king—Shahryar—who, upon discovering his wife’s infidelity, descends into madness. He abandons his realm, roams the countryside, and returns with a vow to marry a new woman each night only to execute her the next morning. This reign of terror devastates the kingdom, threatening its very survival.

Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, volunteers to marry the king. But she has a plan—not only to save her own life, but to heal the kingdom. Each night, she tells the king a story, ending on a cliffhanger to ensure her survival for another day. Yet her storytelling is not merely a tactic of delay. Over the course of 1,001 nights, Scheherazade uses her tales to re-educate the king, to restore his humanity, and to rebuild the moral and political order of the realm.

This narrative arc mirrors the transformation seen in other ancient epics. In The Epic of Gilgamesh, the king of Uruk begins as a tyrant but gains wisdom through loss and journey. In The Odyssey, Ithaca suffers in Odysseus’s absence, and only upon his return is political order restored. Similarly, The Arabian Nights uses storytelling as a vehicle for political healing. Scheherazade’s tales often center on themes of justice, mercy, and wise governance.

Harun al-Rashid and the Paper Revolution

One of the most prominent figures in these stories is Harun al-Rashid, the historical Caliph of Baghdad. His portrayal as a just and curious ruler serves as a model for Shahryar. Harun al-Rashid’s inclusion also anchors the Arabic core of the collection, even as the tales draw from Persian, Indian, and other cultural sources.

Beyond his literary presence, Harun al-Rashid played a pivotal role in the cultural infrastructure of the Arabic world. He established the first paper factory in Baghdad, adopting the Chinese invention of paper via the Silk Road. This innovation revolutionized literature: paper was cheaper and more portable than papyrus or parchment, making books more accessible to merchants and townspeople. The Arabian Nights, with its popular appeal and vibrant storytelling, thrived in this new literary economy.

Indeed, the earliest known fragment of The Arabian Nights dates to the ninth century and is written on paper. The medium helped the stories circulate widely across the Arabic world and eventually into Europe, shaping global literary traditions.

Oral Roots and Fragmentary Beginnings

The earliest known fragment of The Arabian Nights dates back to the 9th century, but it was not a complete manuscript. These early scraps were likely notes for oral storytellers—mnemonic aids rather than literary texts. The first substantial Arabic manuscripts appear in the 14th century, written in what scholars call “Middle Arabic”—a linguistic register that sits between classical and colloquial Arabic. These manuscripts were not standardized and varied across regions, with Syrian and Egyptian traditions adding their own flavors, including poetry to elevate the literary tone and showcase the storyteller’s artistry.

Despite its Arabic title, The Arabian Nights did not originate solely in the Arab world. The frame story itself—featuring Scheherazade, Shahryar, and Dunyazad—likely came from India, with character names of Persian origin. As the tales traveled through Persia, Syria, and Egypt, they absorbed stories from diverse cultures. This multicultural journey gave the collection its eclectic character, but also led to its ambiguous status in Arabic literary tradition. It was often viewed as popular entertainment rather than high literature.

The transformation of The Arabian Nights into a literary classic owes much to Antoine Galland, a French orientalist who traveled through the Levant in the early 18th century. In 1704, Galland published the first French translation of the tales, based on a 14th-century Syrian manuscript known today as the “Galland Manuscript.” This version contained only 221 nights—far short of the legendary 1001.

To meet public demand, Galland expanded the collection by incorporating stories told to him by Hanna Diab, a Syrian Christian storyteller. Initially, Galland transcribed Diab’s tales carefully, but later he relied on brief notes and fleshed out the narratives himself. In doing so, Galland effectively authored parts of The Arabian Nights, shaping its Western reception and literary form.

Ironically, the stories most associated with The Arabian Nights in the West—Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sinbad—were not part of the original Arabic corpus. These tales were either found in isolated manuscripts or told orally by Hanna Diab. Galland translated them into French, and they became wildly popular. In fact, no original Arabic texts have ever been found for Aladdin or Ali Baba, and their Arabic versions are back-translations from Galland’s French.

These stories differ significantly from the traditional Nights tales. They feature more developed characters, richer narrative arcs, and a deeper interest in interior life and moral transformation. Their structure is more novelistic, reflecting the European literary sensibilities of the time—especially the civilizing impulse seen in Charles Perrault’s fairy tales, published in 1697.

A Sea of Stories: The Thousand and One Nights as a Living Tapestry

The Thousand and One Nights is not the product of a single author, but a vast, evolving tapestry of tales shaped by scribes, storytellers, and translators across centuries. The stories were woven together, often from fragments, oral traditions, and other collections—creating a literary mosaic that defies containment.

This process reflects a broader truth: The Thousand and One Nights is a “sea of stories,” where storytellers swim, gather fragments, and reassemble them in new ways. The frame tale—Scheherazade telling stories to survive—is itself a structure that can never fully contain the richness and variety of the embedded tales.

Even within the frame, authority is often reasserted. The Caliph Harun al-Rashid, for instance, appears in disguise to uncover injustice, only to reveal himself and restore order. But the stories themselves resist closure. They spill beyond the frame, endlessly adaptive, endlessly retold.

The tales vary widely—some fantastical, some grounded in everyday life, some drawn from scholarly traditions. New scholarship points to the influence of the Nights on realist writing, including Dickens and George Eliot. Eliot, for example, invokes the Egyptian sorcerer’s mirror of ink in Adam Bede, a direct reference to Edward Lane’s translation. In Daniel Deronda, she structures the narrative around Kamar al-Zaman, again echoing Lane’s retelling. For many European writers, the Nights were not just exotic fantasy—they were a blueprint for realism.

Translation as Authorship: Galland, Burton, Lane, and Haddawy

One of the most influential figures in the Western reception of the Nights was Antoine Galland, the first European translator. When he ran out of material from his Arabic manuscript, he turned to Hanna Diab, a Syrian Christian Maronite from Aleppo. Diab orally shared tales like Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Prince Ahmed and the Fairy Paribanou—stories that had no known Arabic originals before his telling.

Galland didn’t simply transcribe these tales; he refined and expanded them, transforming raw oral narratives into polished literary works. Scholars now view Galland as a literary co-author, and Diab as the original source of some of the most iconic stories in the Western canon.

For example, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves appears to be a fusion of separate motifs—“Open Sesame,” the clever slave girl, and the band of thieves. No complete version of this tale existed before Diab’s telling. He was the first to weave these elements into a unified narrative, which Galland then shaped for publication.

Galland’s translation made the Nights a global phenomenon, but also shaped them through a Western lens. Richard Burton’s 19th-century English translation further transformed the text—not to critique British imperialism, but to push against the constraints of Victorian sexuality. His version is saturated with eroticism and Orientalist fantasy, mobilized as a counterpoint to the moral rigidity of his own culture.

Burton’s translation reveals a deeper tension at the heart of Orientalist literature. In his preface, he extols the beauty of the language and the transporting power of narrative—inviting readers to imagine themselves around a desert campfire, listening to Scheherazade’s tales. But he ends with a startling admission: to colonize a people, one must first understand their language and literature. The tales were not just entertainment—they were tools of knowledge, and knowledge, in the imperial imagination, was power.

Edward Lane (1838) approached the text as a lexicographer and ethnographer. His translation, The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, was heavily annotated and illustrated, offering readers a scholarly window into Arab customs and social practices. Lane expurgated all erotic content and omitted poetry, presenting a sanitized version of the tales. His work was published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, reflecting its educational mission.

Husain Haddawy’s translation, based on Muhsin Mahdi’s critical edition, is notably stripped down—literal and unembellished—yet it beautifully reflects the tone and style of the earliest Arabic manuscript. To the dismay of many readers, Haddawy’s version includes only 221 nights. However, he later published a second volume containing additional stories traditionally associated with the 1001 Nights, drawn from a 19th-century edition.

Take, for example, the description of Scheherazade. In Haddawy’s version, she is portrayed as intelligent, knowledgeable, wise, and refined—having read books on literature, philosophy, and medicine, and knowing poetry by heart. There’s no mention of her physical beauty; the emphasis is entirely on her intellect.

Burton’s depiction is more elaborate. Scheherazade and her sister Dunyazade are introduced with flourish. Burton describes her as “pleasant and polite, wise and witty, well-read and well-bred.” He uses alliteration and rhythm—stylistic flourishes that reflect his ornate prose. In a footnote, he even explains the etymology of their names: Scheherazade means “city freer,” and Dunyazade means “world freer.”

As Jorge Luis Borges observed, every great translator of the Nights becomes, in some sense, its author. Each version—Lane’s ethnographic lens, Burton’s erotic tapestry, Haddawy’s scholarly precision—offers a radically different vision of the same text.

How Many Stories? The Myth of 1001 Nights

The title The Thousand and One Nights was more symbolic than literal—meant to evoke the idea of endless storytelling. Scholars now believe there was likely never a complete version with exactly 1001 tales.

The first complete Arabic edition wasn’t published until 1835, over a century after Galland’s translation. By then, the work had already become a global phenomenon, shaped as much by European literary tastes as by its original oral traditions.

In 1984, Muhsin Mahdi produced the first modern scholarly edition based on the 14th-century Galland manuscript, identifying about 40 stories as the authentic Arabic nucleus. He stripped away later additions—especially Galland’s “orphan tales”—to restore the text’s original coherence.

Most manuscripts contain 200–280 stories, and scribes across regions like Cairo, Istanbul, Damascus, and Baghdad often added tales from other collections to justify the title’s promise of infinity. Just like Galland, these scribes acted as editors—cutting, pasting, and borrowing stories to expand the collection.

Translators like Galland played a similar role, incorporating tales such as Aladdin and Ali Baba, which have no Arabic originals. These “orphan tales” became some of the most famous, shaping Western perceptions of the Nights and influencing literature and film worldwide.

In essence, The Thousand and One Nights is a living, adaptive text—built through centuries of storytelling, editing, and cultural reinvention.

Oriental Splendor and the Power of Fantasy

The European reception of The Arabian Nights—or Alf Layla wa Layla—was not simply a literary event. It marked a cultural turning point that sparked widespread fascination with the “Orient,” reshaping Western ideas of storytelling, exoticism, and empire. Thanks to Antoine Galland’s early 18th-century French translation, Les Mille et Une Nuits, a new genre of Oriental tales emerged, captivating readers with visions of magical realms, enchanted objects, and unimaginable wealth.

Galland’s translation introduced European audiences to a world of fantasy and wonder. The tales featured flying carpets, treasure-filled caves, and genies bound to lamps—elements that evoked a sense of Oriental splendor far more seductive than the stories themselves. This imagined East became a literary playground, a realm of excess and enchantment that fueled the rise of Orientalist fiction across Europe.

The Sinbad cycle, with its seven voyages, stands out as a blend of adventure and ethnography, resembling travel accounts like those of Ibn Battuta. These tales offered European readers a glimpse into distant cultures during a time of colonial expansion and global curiosity.

Central to this appeal was the frame tale structure: Scheherazade’s nightly storytelling to delay her execution. This narrative device emphasized the life-giving power of storytelling—its ability to enchant, to transform, and to defy death. It was this meta-narrative, this celebration of storytelling itself, that gave The Arabian Nights its enduring resonance.

The Thousand and One Nights as World Literature

The Thousand and One Nights stands as a paradigmatic example of world literature—especially if we define world literature as the movement of texts across time, space, and cultures. Its cosmopolitan provenance and global circulation make it one of the most widely disseminated literary works in history.

Open any anthology of world literature, and you’ll likely find selections from The Arabian Nights. These are often drawn from the so-called “original Arabic cycle”—the core set of stories considered authentic by scholars. Yet paradoxically, these tales were never regarded as canonical or high literature within the Arabic-speaking world. The language was seen as unrefined, the poetry lacking in formal elegance, and the stories themselves more folkloric than literary.

Meanwhile, the stories that truly circulated and captured global imagination—Aladdin, Ali Baba, Sinbad—are conspicuously absent from these anthologies. Why? Because they were added later, in French, and possibly co-authored by Hanna Diab, a Syrian traveler whose oral storytelling shaped Antoine Galland’s 18th-century translation. These tales exist outside the Arabic manuscript tradition, and their placement in literary history remains ambiguous. Should they be classified under French literature? 18th-century Orientalism? Or world literature?

This tension reveals two competing conceptions of world literature:

- One sees world literature as a curated collection of representative texts from national traditions—hence the preference for the original Arabic cycle.

- The other views world literature as a set of texts that circulate, adapt, and transform across cultures—suggesting that the peripheral, hybrid, and late additions deserve equal attention.

Take The Sleeper and the Waker, a tale that echoes Shakespeare and Calderón’s Life is a Dream. It would seem a natural fit for world literature, yet it’s excluded for being a late addition. Instead, we get The Porter and the Three Ladies of Baghdad, which is harder to connect to other texts in a typical world literature syllabus.

Scholars of Arabic literature have coined the term “Arabian Nights syndrome” to describe the over-representation of the Nights in public discourse and popular culture. From The Thief of Baghdad to countless film versions of Aladdin and Ali Baba, these stories have become cultural icons—often detached from their literary origins.

Yet within the Nights themselves, there is vast diversity. Some tales are fantastical, others grounded in everyday life. Some emerge from scholarly traditions, others from popular oral storytelling. New scholarship even traces the influence of the Nights on realist writing—on Dickens, for example, who found inspiration in tales of merchants, cobblers, and tailors. George Eliot, too, drew from the Nights. In Adam Bede, she invokes the image of the Egyptian sorcerer’s mirror of ink—a direct reference to Edward Lane’s translation. In Daniel Deronda, she structures the narrative around Kamar al-Zaman, again echoing Lane’s retelling.

For many European writers, The Arabian Nights was not a gateway to the irrational or the exotic—it was a blueprint for realism. It taught them how to write about ordinary people, complex relationships, and layered storytelling.

So Professor … suggests to resist the simplistic equation: Arabian Nights = Orientalism = Supernatural. The truth is far more complex. The Nights are a sea of stories—fluid, adaptive, and uncontainable. Their frame tale may promise order, but the tales themselves overflow with contradiction, transformation, and possibility.

Patriarchal Society, Female Heroism, and Punished Curiosity

The text of a patriarchal society creates a heroine—and gives her a younger sister who watches everything unfold. Scheherazade’s role as a heroine deserves deeper examination. She has been celebrated for centuries as a savior of womankind, and that’s a fair assessment. But she’s not revolutionary in the traditional sense. She doesn’t overthrow the system. Instead, she uses her narrative gifts as therapy for the king—a “talking cure.” Scheherazade talks him out of madness. She brings him back to the world—but again, it’s a world that returns to the status quo. The world she restores is the same one that existed before.

At the end, she is married. The 19th-century versions emphasize that she bears three children, and it’s those children she uses as collateral to secure her safety. Her power lies in her intellect, her storytelling, and her ability to heal—but not in changing the system itself.

Dunyazad, her younger sister, plays a crucial role as the listener—a model for how to receive stories, especially for a king who has lost the ability to understand narrative, perhaps even language itself. She steps in as the ideal audience, helping reestablish a sane and balanced relationship between storyteller and listener. It’s no accident that Scheherazade ensures Dunyazad is present on the night she marries the king. It’s a strange situation—almost a form of indoctrination for a young girl—but necessary to demonstrate how narrative functions and how it can be received.

Harun al-Rashid, the great Abbasid Caliph, is a historical figure who appears throughout The Thousand and One Nights. He’s both a tyrant and an enthusiastic seeker of stories—a blend of Scheherazade and Dunyazad. He constantly asks people to tell him their stories, sometimes at great personal risk. His curiosity is dangerous, as the tales often warn: “Ask not what concerneth you not, lest you hear what pleaseth you not.” But as Caliph, he’s protected from the consequences. He embodies the desire to hear what lies beyond one’s world—the hunger for narrative.

In the world of The Thousand and One Nights, curiosity is punished. People are told not to ask questions. But if you don’t ask, you’ll never hear the great stories. And sometimes, telling a great story can redeem a life nearly lost to that very curiosity.

The Power of Storytelling and Endless Adaptation

As narrative constructions, these stories reveal so much about the power of storytelling—about how we listen, how we interpret, and how narrative itself can shape perception, identity, and even sanity.

The Thousand and One Nights becomes a source of inspiration for generations of writers who reimagine its characters and themes within entirely new historical and cultural contexts. The adaptations are as diverse as they are revealing:

- Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade” is a brilliant, ironic parody in which Scheherazade tells stories not of fantasy, but of real inventions and scientific marvels—submarines, microscopes, and hot air balloons. The king, unable to believe these “fantastical” truths, executes her. Ironically, the only story he believes is the one that’s entirely fictional. Poe plays with the boundaries of truth and fiction, and the consequences of disbelief.

- Théophile Gautier offers another take in his own “Thousand and Second Night.” In this version, Scheherazade has run out of stories. Desperate, she stumbles into Gautier’s opium-laced parlor and begs him to tell her one. But the story he offers fails to save her, and she too is executed. Her sister is left mourning, clutching a blood-spattered handkerchief. It’s a haunting meditation on the limits of narrative and the exhaustion of imagination.

- Naguib Mahfouz, the Egyptian Nobel laureate, wrote Arabian Days and Nights, using characters from The Thousand and One Nights but abandoning their original storylines. Instead, he repurposes them to explore contemporary Egyptian politics and history. By embedding modern concerns within this ancient, venerated text, Mahfouz is able to speak about things that might be too dangerous or controversial to address directly in a realist form.

What’s extraordinary about The Thousand and One Nights is its adaptability. It absorbs and reflects the values, anxieties, and aesthetics of countless cultures. It’s a narrative architecture that accommodates endless reinvention. And in doing so, it reminds us that storytelling is not just entertainment—it’s a way of thinking, a way of surviving, and a way of transforming the world around us.

Conclusion

In sum, The Arabian Nights is far more than a collection of fantastical tales. It is a political allegory, a cultural bridge, and a testament to the transformative power of storytelling. Through Scheherazade’s voice, literature becomes a tool of resistance, education, and restoration—proving that stories can save lives and rebuild kingdoms.

The Nights exemplify the fluidity of storytelling across cultures and centuries. What began as a set of oral tales evolved through translation and adaptation into a literary masterpiece that continues to enchant readers worldwide. Its journey—from the bazaars of Baghdad to the salons of Paris—reveals how stories can transcend borders, languages, and genres to become part of our shared human heritage.

Ultimately, The Arabian Nights is a mirror—reflecting the desires, fantasies, and ambitions of its readers. In 18th- and 19th-century Europe, it offered a vision of the East that was by turns enchanting and exotic. Yet it also raised deeper questions about storytelling, translation, and the politics of cultural representation. Its enduring appeal lies not only in its magic, but in its ability to adapt, to travel, and to reveal as much about its interpreters as about its origins.